Everyone talks about how stretching forward and downwards towards the bit is good for the horse, but actually being able to do it correctly is not so easy. Knowing the “how, why and when” all comes into play and are important factors to riding, or training, a correct forward downwards frame. Dr. Britta Schöffmann explains everything.

Summary

- How should the stretching posture look like?

- Why it is so important

- Requirements

- Typical mistakes

- How much is enough

- The willingness to stretch

- Managing problems

- Are there any negative effects?

How should the stretching posture look like?

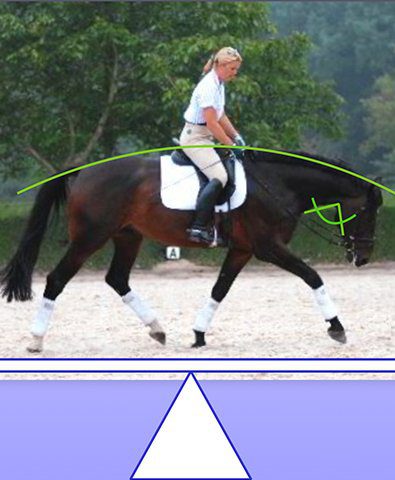

- A slightly convex topline, definitely not just a round neck with the nose behind the vertical.

- The following hind leg. This means: The supporting hind leg should step under the body, landing as close as possible to the horse’s centre of gravity.

- The rider feels pressure on the bit, however, this is more of a gentle pressure, than the horse leaning on the hand, or using the bit as a crutch.

- A forward-downward stretching always occurs with forward motion. There is no forwards and downwards when standing still. But keep in mind: The forward being referred to is the tendency of the horse’s nose. By opening the angle between the neck and the jowls and opening the poll, the nose naturally pushes forward.

- The horse is in balance and in self-carriage, the rider only sets the frame with a light and a steady contact.

Why is it so important?

‘Working with the correct forward and downward stretching supports and maintains the willingness to stretch and stabilizes the back and the topline’, Dr. Britta Schöffmann explains. But for the exercise to have a health-promoting effect, correct execution is important.

What are the requirements?

The horse needs to be relaxed: An excited or tense horse will not let his neck fall forward and down with confidence, ‘but will want to get an overview of the surroundings by lifting his neck. Mental and physical relaxation is therefore necessary.’

A second important point is balance. ‘The horse must be able to carry himself and balance his body in such a way that he moves in balance’.

What are the mistakes to avoid?

A lot of things are considered as forward and down, as soon as the horse lowers the head/neck area, riders like to talk about it. Here are some examples of typical mistakes:

- The top line is not curved, but straight.

- The horse moves with his nose behind the vertical.

- The hindquarters do not connect, the horse looks a little like a duck swimming, pushing with his back legs out behind him, rather than stepping under the center of gravity.

- The horse moves on the forehand, moving visibly downhill.

How much is enough?

This really depends on the horse’s type & natural abilities.

The often-cited guideline is the point of the shoulder – this is the height at which the horse’s nose should reach to. However, Britta Schöffmann says that ‘the stretching really only begins once the horses nose is at the same height as the point of the shoulder’. It is almost impossible to say there is only one answer.

There is no exact rule, it has to be adapted to every particular horse and how he moves and is put together.

‘I wouldn’t ask a horse with a sway back to go too far down’ explains Britta S. However if you have a horse under you that has, for example, a high set neck and is naturally very balanced ‘then makes sense to allow them to stretch their nose further down than the point of the shoulder. What is more important is that he doesn’t lose his balance’

The willingness to stretch is important

It’s necessary for the horse to be willing to stretch forward and downwards by himself, you should not have to hold him there with your hands. There are two key elements in forward downwards that one needs to be aware of- the willingness to stretch and being able to hold this position, we should really refer to these rather than just forwards downwards.

Britta Schöffmann’s definition of this is as follows: ‘Willingness to stretch is the horse’s effort to stretch its neck whilst moving- on the lunge or under the rider- and allowing his neck to fall whilst slightly lifting his back, with a tendency to stretch forward and downward towards the bit.’

The importance of this is related to what happens when the horse actually stretches: The nuchal ligament and supraspinous ligament, which extends from the occipital bone to the tail, joining one another in front of the wither, connect the spinous processes. If traction is added by lowering the head, this stretching movement will fan the spinous processes, especially in the area of the withers, slightly forward and straighten them up a little. It is precisely this change that helps the horse to carry the rider’s weight better.

If things do not go as planned

When the rider initiates the horse to stretch, whilst asking him to actively track up behind, the horse should ideally follow the yielding hand and remain in front of the supporting leg. But what do we do if the horse does not stretch consistently, but continues to come up above the hand again and again?

Under no circumstances, should you fidget and pull with your hands. As Britta very clearly says ‘there is no aid that is known as the fidget him round aid!’

When this happens the horse is only telling us that something is still not working properly in the preparation or general training. The rider should simply keep riding and offer it again and again. A smart way to help the horse is lots of transitions, especially trot to canter transitions, creating the perfect opportunity for the horse to be ready to stretch. ‘The change from taking a little more weight and moving a little more towards the hand improves the willingness to stretch,’ explains the trainer. ‘Good bending work also promotes the willingness to stretch.’ The few good moments at the beginning, when the horse shows an ideal stretching frame and the back swings, would be offered more and more in the course of the training, and at some point the consistency and ability to remain in this stretching frame would also be there. Britta Schöffmann says that, in general, the following is true:

‘The willingness of the horse to stretch forwards and down is not a fixed entity, but a very sensitive and fluid construction. Incorrect implementation (and unsuitable equipment of any kind) can severely curb this willingness, if not entirely destroy it – at the expense of a healthy and sound back’.

Can forward downward stretching have negative effects?

In the classical Baroque and Portuguese disciplines, there have been a lot of discussions recently as to whether the forward downward stretching is generally more harmful than useful. For Britta Schöffmann this is absolutely incomprehensible. ‘For me, the biomechanics of the horse gives the meaning of forwards and down’. However, it can be harmful ‘if it becomes a means to an end in itself’, explains the trainer. To work for an hour only in a forwards and downwards direction would be a misunderstood idea. ‘Forward downwards is simply a piece of the puzzle that is forward downwards! Abdominal muscles and the top line must be allowed to work.’ The right thing to do is to keep offering opportunities – both in the warm-up phase and during the working phase.